Chief operator: Mingo Junction Wastewater Facility ‘one of the best’

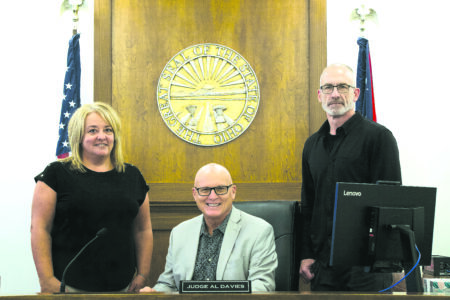

Photo by Christopher Dacanay Kyle Moffat, chief operator of the Mingo Junction Wastewater Department, stood above the village wastewater treatment facility’s two “ditches” for separating water from raw sewage.

MINGO JUNCTION — Most individuals pay no mind to the water they’ve used after it runs down the sink drain. Yet for employees at the Mingo Junction Wastewater Facility, how that water is treated before it re-enters the Earth is critical.

Like other wastewater treatment facilities, the plant’s job is to collect wastewater — including storm water and raw sewage — and process it into clear water that’s suitable for discharge into the environment.

The plant is designed to treat up to 3 million gallons per day, though it averages about 600,000 gallons per day. It’s a Class II wastewater treatment facility, receiving its classification from the Environmental Protection Agency. Largely determined by the facility’s size, a plant’s classification dictates the acceptable levels of certain contaminants that can be present in processed water.

Issuing permits every five years, the EPA determines the standards a plant must meet to ensure water is suitable for discharge. In Mingo Junction, certified employees are required to test water regularly for qualities including pH level, temperature, biological oxygen demand and total suspended solids. Testing results are submitted to the EPA monthly in an electronic discharge monitoring report.

According to Kyle Moffat, chief operator of the Mingo Junction Wastewater Department, the plant is permitted by the EPA to discharge water with 30 parts per million, or 30 milligrams of solids per liter of water.

Additionally, the EPA mandates plants operate at an 85 percent solids removal rate.

Mingo Junction’s plant meets those standards and then some, currently averaging 85 percent removal and four parts per million, Moffat said.

With years of experience in the wastewater treatment field, Moffat said he’s seen how other plants operate. He added that Mingo Junction’s plant — which has been graced by a number of improvements within the last five years — runs “super efficiently.”

“In my opinion, this is one of the best running plants in the Valley,” Moffat said.

The goal of treatment is separation — getting the water as clear as possible before disinfecting and discharging it.

Mingo’s plant takes in wastewater from all over the village, Moffat said. Two years ago, to comply with EPA regulations, the village added controlled separation in certain areas to differentiate between sewage and stormwater, with the latter diverting straight into Cross Creek.

Piped into the plant, raw sewage drops into an underground “wet well,” where a screen filters out large objects. “Composite samplers” take automatic tests 24/7 to measure the sewage’s contents. Once the well is full enough, three alternating raw pumps send the material to its next stage, constructed two years ago.

Built for $5.2 million, the building is attached to a 1 million-gallon equalization basin, that automatically catches overflow from the pumps. Inside the building is a grit separation machine that uses a corkscrew to filter out small particles like gravel, rags, paper and even lumps of grease.

A pipe uses gravity to transfer sewage into two tanks known as “ditches,”where the water and sewage separation primarily occurs.

Running constantly, each ditch is filled with 310 fine diffusers, which make oxygen bubbles that aerate the sewage. This is good for the bacteria that break down the sewage, and it keeps the contents from stinking, Moffat said.

Sewage circles around the ditches like a “race track,” Moffat said. Flow-directing “baffles” on the bottom help separate the contents, causing water to float and heavy sewage to sink. Water jets aid in skimming solid matter off the top. That matter is collected and sent to drying beds, where trickle filters capture the water and cycle it back into the plant.

Thick sludge that’s collected at the ditch’s bottom is fed into a 150,000-gallon digester. Diffusers once again blow bubbles, which make the sewage rise. Water that becomes separated is cycled back into the plant.

“Anything that’s in this plant, if it hits a drain, it goes back to the beginning, starts the process again,” Moffat said.

Matter in the digester gets thicker and thicker. It must stay there for at least 180 days before being hauled away to an EPA-approved farm for use as an agricultural spread, promoting soil nutrients. In September, Mingo’s plant had 120,000 gallons of sludge hauled.

Meanwhile, clear water in the ditch that’s risen to the top is piped into the contact tank — a pivotal area, for the EPA’s purposes. There, water enters a snaking tunnel where chlorine is added to kill bacteria.

Flowing for 45 minutes, the water then enters a box where a proportional amount of bisulfite is added to eliminate the chlorine. Another composite sampler takes tests here, giving the plant its percent removal.

After about 12 hours of processing, water is piped directly into nearby Cross Creek, just upstream from the Mingo Junction Marina. As per the EPA, Moffat said, a small amount of chlorine remains to keep algae growth minimal, though the local fish are still happy and enjoy swimming around the pipe.

The plant’s efficiency is aided by IT experience from Moffat, who developed software to store testing results and other data related to inward and outward flow. He’s also had computers synced between his home and locations in the facility, so adjustments can be made remotely.

“Maintenance and being committed” also play a big role in the plant’s continued success, Moffat said. Employees regularly keep pipes clean and thoroughly clean the large tanks once per year. An industrial vacuum is used to help with clogs, which can be caused by flushable wipes. Moffat encouraged village residents not to use these, as they can harm residential and plant lines.

The department takes pride in maintaining its grounds and repairing its buildings, which recently received a new coat of paint, Moffat said.

Besides the $5.2 million enhancement two years ago, the plant has seen $860,000 come from the village over the last five years, with funds being used to upgrade equipment like pumps, mixers and digester materials. Moffat credits the improvements to the village’s previous administration, which approved the investments.

“In general, everything has been replaced,” Moffat said. “What you’re looking at now is basically a brand-new plant, within the last five years.”

He added later, “The main thing I want to stress is that the village has let me do every improvement that I’ve seen needed to be done, and they have been in full support of everything that’s done at this plant. … It’s almost brand new again because they let me do it.”